Reading Sample

Reading sample

[p 16-19]

“So that means I’m dead,” I remarked as blandly as I could and observed the other people around us, who were either still sitting on the bleachers with calm and unfocused expressions or standing up and heading towards the train. They were dead, too, it stood to reason. In a different way, of course, but as dead as dead could be. My next logical deduction took the shape of a question for the Old Man: “Is this heaven?”

The Old Man answered with a question in turn: “I don’t know. Is it?”

“Heaven should be…” I searched for the right word for a few moments before coming up with a suitable adjective, “more paradise-like. There should be nature and waterfalls and… I dunno,” I shrugged. “It should be a place you’d like to come to.”

“Then this consequently isn’t heaven,” the Old Man said gently, making no effort to change my mind.

I looked over at the train again. “Where does it go?”

“I don’t…”

“Does it take you to paradise?” I interrupted.

“I don’t…”

“Does everyone have to get on board?” /---/ Getting on the train frightened me because it would have meant my death was final, and if I had no idea what was waiting at the end of the trip, then did I really want to see it? Not knowing was scary, but the Old Man surprised me by answering no.

My attention took a sharp turn from the train and the other people to this new topic. “What do you mean?” I asked curiously.

“You don’t have to board the train. But I recommend it.”

I snorted. “But I don’t want to. And if you say I must, then I want to know what my other options are.”

The Old Man thought for a moment, then said: “You can look back over your life and…”

I didn’t even let him finish his sentence before interrupting: “Yes!”

“But…” the Old Man tried to add something, but I shook my head vigorously. No, no, no! I didn’t want to hear another word! The Old Man couldn’t mention the option and then take it away. “I want to look over my life,” I said confidently, reckoning one reason was that I now knew at least a little bit about who I am and had a sense of what my life was like. At the same time, whereas a train ride into a white void is terrifying and unfamiliar, I do know and recognize my own life. There wouldn’t be anything unanticipated. And although I didn’t actually remember everything, my mind was bursting like floodwaters waiting behind a dam and my head started to fill up with thoughts, memories, and wishes. Death is ultimate unknowing. By looking back over my life, I might gain a better understanding of who I was. Of who I am. The Old Man couldn’t take that opportunity away from me! I demanded: “Show me my life!”

The Old Man accepted my wish, though I could see he was reluctant to do so. Still, I gave him no choice. I wanted to see! The Old Man approached, rested a hand on my shoulder, and pressed lightly for me to sit back down onto the bleacher. His touch unleashed a stream of images in my mind. Flickers of situations I thought I knew flashed through my head, but this time I didn’t experience them directly. Rather, I was floating somewhere above the scene and observing the past I’d made for myself.

There were memories from the time before my brother had even been born, and then a memory from a party that had been a total fiasco a few months back. A fight with my parents and Grandma’s funeral, during which I secretly chatted with my friends online. It all flashed through my mind so quickly that I didn’t have a chance to record every individual moment, though each did leave some imprint, some impression on my memory. Two words started to run on repeat in my head: arrogant and egotistical. They sounded foreign and I tried to shake them, but couldn’t. The images and memories kept coming and coming until I finally almost pulled away from the Old Man’s hand. The memories yielded and no more new ones forced their way into my head; still, the ones I’d already seen had been enough.

I leapt to my feet as if stung.

Shaking and panting, even though I didn’t have to breathe in that place, I glared at the Old Man. “That’s not my life!”

His attitude was suddenly unpitying. “Was it not what you thought you would see?”

“That’s not my life!” I repeated. The memories had been so disturbing that I resolved riding the train off into the unknown would be better than watching the warped film that was supposedly my past. “I’m getting on the train,” I announced to the Old Man, but he shook his head.

“You can’t.”

“What do you mean, I can’t?” I demanded, raising my voice.

“You can’t. You already agreed to look at your life. You can’t go on anymore,” the Old Man said plainly.

Translated by Adam Cullen

[p 148-151]

Finally I was back in my own body, standing in front of my two brothers, listening as Jaanus confidently informed me, "You won't phone Mum."

I clamped my mouth shut to stop me from saying or doing what I'd done the last time. Although to be frank I didn't know what else to do. I wasn't the kind of girl who always rushed to comfort or soothe a little kid. I put up with them because… I had no choice. And now I was in a spot because I didn't want to do what I'd done before and threaten them with monsters. I had the strange feeling that that wouldn't count as righting my wrong. But I didn't want to call Mum either and admit defeat. /---/

I racked my brain for what to do, and then I remembered what the Old Man had been saying to me as he brought me here. We'd been talking about playing. Playing… Did he want me to play with my brothers? Was that what I'd done wrong? I hadn't played with my brothers? I groaned audibly.

Of course. It now seemed entirely logical that that was exactly why I'd been brought here at a moment like this, but why did it have to be such an awkward one? There were umpteen times we'd chilled in the house, but no – the Old Man had selected the time when I was ill, when my brothers were ill. Had he ever tried playing with two poorly children, especially with a splitting headache of his own?

I turned my gaze upwards, trying to focus on the idea that the Old Man was up there somewhere. "Take me back," I said in my mind, but nothing happened. I knew it wouldn't help, but leastways I had to give it a shot.

I sighed again. Great, now I needed to think how to play with the pair of them. /---/ Where to start… I closed my eyes, trying to summon up a kids' film or at least a comic, but instead what I recalled dimly was when I'd been a kid myself and Dad had played with me… hadn't we played pirates once?

I could have shouted for joy when the idea leapt into my head but of course what I needed was a sad face, which I managed to pull of masterfully. "Well, if you don't want to, that's fine. But children who are ill are not allowed aboard the Pirate King's Ship."

I set both their mugs on the table with a thud and raised my own. "I definitely want to go. Sail to foreign lands, do battle with the sea dogs, and dig up treasure and gold!" With a swashbuckling slurp I drained my mug and announced over the din from the TV, "Fantastic! I'm cured! The pirate ship awaits!"

My brothers eyed me suspiciously, perhaps with some genuine curiosity, but their hands did not reach for their mugs.

Whistling all the while I ignored them and strutted into the dining room where they couldn't see me from the sofa. There I began to kick up a thundering racket. Still whistling, I lugged the table into the middle of the room and hauled the chairs around. At one point I needed pillows so I strutted back into the living room, listening to two pairs of feet suddenly scuttling pit-a-pat back towards the sofa. I stopped for a moment, and when I stepped into the room, my brothers were already looking innocent under the blanket.

"I'll take those. And those. The blanket can be the sail and the pirates will need pillows. Kevin, you sit here, I'm taking the pillows: the sofa is soft enough as it is. The ship isn't."

I went back to building the ship. Three minutes later, Jaanus's nose poked into the dining room, his eyes greedily taking in the ship constructed out of the chairs and the table.

"I want to go on the pirate ship too," he said.

I crossed my arms and shook my head. "No! Ill children are not allowed aboard the pirate ship. What if you got worse?"

"But I want to be a pirate," mumbled my brother.

"No. No. No." I said sternly and turned my back on him. Jaanus went back to the living room and then I heard some slurping. I smiled. It was working!

A moment later Jaanus dashed back into the dining room, "I've drunk all my tea!"

Translated by Susan Wilson

[p 184-187]

"Merita!" I heard a voice and jumped up. Who was that? Who knew my name?

"Merita!" the voice was now calling happily and I watched a boy of about ten years of age weaving between the people as he ran towards me.

"I can't remember the last time I dashed about like that," panted this completely unknown child before he cheerily went on, "It's so good to run and not be in a wheelchair. Wheelchairs are amazing, but the nurses don't like it when we meet a wall. You can't always get past. And everywhere you go you seem to meet one!"

He smiled. One of his front teeth was missing. As were his eyelashes, eyebrows and hair. His whole body was a glow of dark blotches. "Cancer. Leukaemia," flashed through my mind. Last time I'd learned to recognise illnesses.

"You are Merita, aren't you?" he asked.

I nodded and cautiously ventured, "How do you know who I am?" Although I didn't have the world's greatest memory for faces, I was 100% certain that I'd never seen this boy before.

The boy did not apparently hear my question because he sighed happily and continued as before: "Oh, how fantastic. I was scared it wouldn't work. When I found out I was going I kept saying 'Merita, Merita' over and over again and I'm sure my Mum and Dad thought the drugs had made me go crazy. " /---/ The boy laughed out loud before chattering on, "Anyhow, when I got here I realised straight away I was in the right place and I shouted your name hoping you'd hear me and look, I've found you!"

Ahhaa. Great that he's here, but it cast no light on how he knew me. To say nothing of the fact that I still had no idea who he was. The boy himself must have finally realised because he sighed and slapped his hand to his head before extending it towards me. "I forgot! I'm Stephen, I completely forgot I would need to introduce myself."

"Lovely to meet you," I tried to be polite, shook his hand and then asked again, "But how do you know me? We haven’t met before, have we?"

The boy roared with laughter. "Oh, I forgot that too! I was in the same hospital as Jeremy and we were on the same ward and made friends and then they took him to another ward, but after his operation he came to visit me and he told me about you."

"Jeremy," I repeated the name. The glimmer I'd talked to. /---/ "He talked to you about me?"

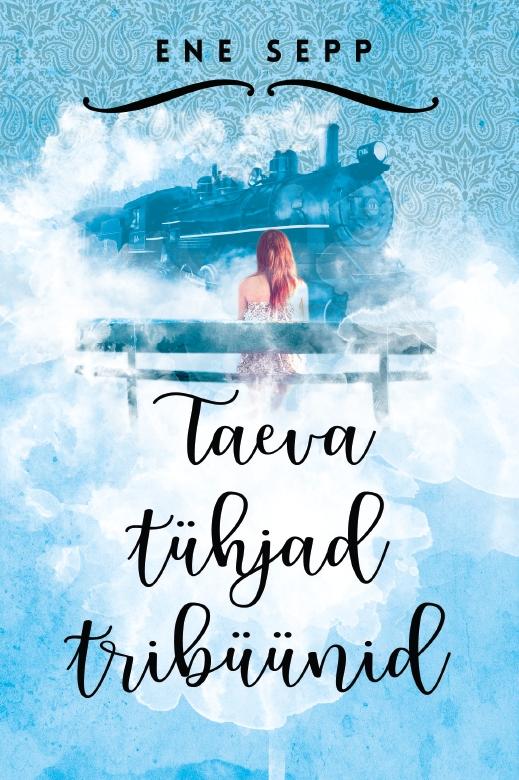

"Yeaaahh! He nearly died during his operation and then he came here er…… glimmering and he said that you'd told him that's what he was doing. And he talked to you and when he stayed alive, when he got better he told me that he'd been to a white place somewhere up high where there was a sky-blue train and a bloodstained girl who helped people to board the train and move on." /---/

"I can't believe he told you that," I shook my head.

"Why not?" asked Stephen. "It's really cool, he said that if I realise I'm going I should say your name over and over because I'd come right here. He wasn't sure if it would work but he said I should try it and see because there was nothing to lose."

"Did he say why you should?" I was puzzled. Why would anyone talk to a dying child about a girl in blood-stained jeans?!

"He said it was a dare and if I got here then it would make things easier for me because you're… cool. /---/ He said you would encourage me and help me to accept what's happened and… and he said if it worked, then I had to say hello to you."

Stephen fell silent and then added awkwardly, "Sooo… hello from Jeremy."

Translated by Susan Wilson